PHILEMON: PAUL’S LOVING APPEAL

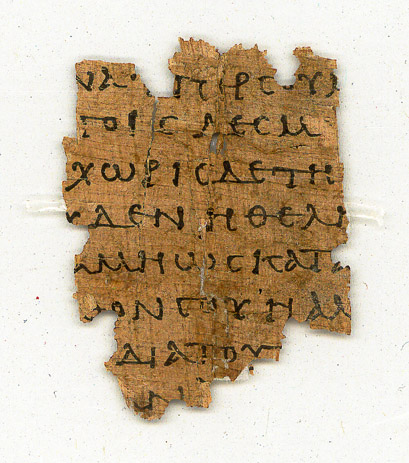

The earliest known fragment of the Epistle to Philemon, believed to date to the late 2nd or early 3rd century.

GNU Free Documentation License

Wikimedia Commons

BY

JIM GERRISH

Light of Israel Bible Commentaries

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from: The Holy Bible: New International Version®, NIV®, Copyright© 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by the International Bible Society. Used with permission.

Copyright © Jim Gerrish 2019

INTRODUCTION

Philemon is a tiny book that was probably written on a single sheet of papyrus. It is a precious little book, since it is the only private letter written by Paul that we possess today.1 Through history, this little book has scarcely been questioned as a genuine letter of Paul. It is felt by most commentators that it was written while he was a prisoner in Rome (c. AD 59-62), and was sent out with the other “prison epistles” of Ephesians and Colossians. Likely the prison epistle of Philippians was sent at a later date. The epistle of Philemon was probably carried to the Lycus Valley churches by Tychicus and by the slave Onesimus himself (cf. Eph. 6:21; Col. 4:7-9).

This short letter is addressed to Philemon, who was a dear friend of Paul. Philemon was likely a resident of Colossae. It is also addressed to Apphia, who was probably his wife, and to Archippus, who was likely his son. Philemon, who earlier was won to the Lord by Paul, was apparently a wealthy and influential person in the church. His house was obviously large enough that the church meetings were conducted there.

At the core of the problem in this letter is Onesimus, the runaway slave of Philemon. Onesimus in his flight had somehow arrived at Rome and had come into contact with Paul. In doing so, he was won to Christ by the apostle. He then began to diligently serve Paul in the latter’s imprisonment, to the point that the apostle could hardly do without him. However, since he was a runaway slave, Paul was determined to send him back to his master.

This letter, which he carried back to his owner, is in itself a masterful appeal that Onesimus should be received as a brother in Christ and that he could now become useful to Philemon, and perhaps still to Paul himself. The letter shows how Christianity was already making drastic social and cultural changes in the otherwise cruel Roman Empire.

Philemon is a bright light focused on human relationships in the First Century after the advent of Christianity. Today it sheds light on our human relationships at home, at church and in our communities, especially as we relate to employers and fellow workers.

CHAPTER 1

Paul, a prisoner of Christ Jesus, and Timothy our brother, To Philemon our dear friend and fellow worker— Philemon 1:1

We should note here that in this letter to a dear friend, Paul drops his usual title of “apostle.” Rather, he calls himself only a “prisoner.” Clearly, it is evident that Paul has his faithful helper Timothy at his side while writing.

It is helpful for us to remember that during his Roman imprisonment, of about two years, Paul was able to live in his own rented house and was free to receive guests (Acts 28:30-31). However, there is clear evidence that he was still bound to a Roman soldier during this time (Acts 28:20; Eph. 6:20; Phil. 1:13). Paul knew that freedom was not an absolute right or necessity and that even in bonds he could fulfil his destiny.1 In the last analysis, Paul was a prisoner of Christ and not of Rome. Ambrose (fourth century) once said: “…It is more glorious for us to be bound by him than to be set free and loosed from others.” 2

As we have mentioned, Paul’s beloved Timothy was with him in his writing and here greetings were sent from him. As we no doubt remember, young Timothy joined Paul on his Second Missionary Journey (Acts 16:1-3) and continued with him for the rest of Paul’s life. He was probably converted under the apostle and was like a son to him (1 Tim. 1:2). Timothy had a Jewish mother and a Gentile father and was thus perfectly suited to help Paul take the Jewish gospel to the Gentiles.

The addressee of this letter is Philemon, a dear friend of Paul and also one who had apparently worked together with the apostle at some point. This is the only mention of his name in the New Testament so we do not know how or when they labored together. By the fact that he was a slaveholder and had a house large enough to accommodate the church, we can assume that he was probably a wealthy and influential person. The name Philemon signifies a loving person and in all likelihood he was just that.3

Paul continues to write, “also to Apphia our sister and Archippus our fellow soldier—and to the church that meets in your home:” (1:2). Commentators generally feel that Apphia was the wife of Philemon. Since Paul will be dealing with a runaway slave from the household, it was appropriate that he address Apphia. According to the customs of those days the wife had the daily responsibility for the slaves.4

Next, Paul greets Archippus, who is likely the pastor of the house church. The traditional view is that he was the son of Philemon and Apphia.5 In Colossians 4:17, Paul challenges Archippus to complete his ministry. He had no doubt also worked closely with Paul at one point and thus is called a fellow soldier (Gk. sunstratiōtēi). If we are indeed dealing with the Colossian church, as many suppose, it is important to note that Paul apparently never visited Colossae (Col. 1:1-8; 2:1). The church was founded by Epaphras (Col. 1:7), whom Paul mentions as a fellow prisoner in verse 23. No doubt, the church was founded as a result of Paul’s great work and outreach at Ephesus. It is possible that Archippus replaced Epaphras, who traveled to help Paul in Rome.6

We should say a little about the church, or rather house-church (house-churches) at Colossae. The word for church is the Greek (ekklēsiāi), which is made up of two words ek and kalaō, meaning those “called out.” This word was used in the Greek world to describe any kind of an assembly.7 There is very clear evidence that the churches in each city met in the homes of the church members and not in some dedicated building (cf. Acts 5:42; 20:20; Rom. 16:5; Col. 4:15). Interestingly, church buildings did not appear until the third century.8 This was long after the era of the church’s greatest vitality.

Several commentators have noted that this letter is more of an open letter to the church rather than just a personal one.9 The church was in the background listening to this letter and if that is truly the case, it would have placed a considerable amount of pressure upon Philemon to do the right thing.

“Grace and peace to you from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ” (1:3). Here Paul gives his traditional blessing of grace. We never tire of reminding ourselves that grace must precede peace. If God’s grace has not been extended to each of us in a full salvation through Jesus, there will be no real peace.

PAUL’S THANKSGIVING AND PRAYER

I always thank my God as I remember you in my prayers, because I hear about your love for all his holy people and your faith in the Lord Jesus. Philemon 1:4-5

Paul kept regular hours of prayer as did most Jewish people.10 It is clear that he prayed a lot and that he prayed continually for people and churches all over the Greco-Roman world. The apostle had heard about the love of the Colossian church. Again, this is an indication that he had not been there personally.

Their love had been declared all over, just as the love of several other churches in the First Century. Today it seems that some churches have become almost famous for their discord and fighting rather than their love. The church father Tertullian around AD 200 reported what the pagans were saying about Christians: “‘Look,’ they say, ‘how they love one another’ (for they [the pagans] themselves hate one another); ‘and how they are ready to die for each other’ (for they themselves are readier to kill each other).” 11

After all, this was the New Commandment that Jesus had given to his churches. He had said, “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another” (Jn. 13:34). C. S. Lewis once said: “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket – safe, dark, motionless, airless – it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable.”

“I pray that your partnership with us in the faith may be effective in deepening your understanding of every good thing we share for the sake of Christ” (1:6). Baptist professor, Bob Utley remarks: “This verse has been interpreted in several senses. 1. the fellowship of believers with each other (cf. 2 Cor. 8:4; Phil. 2:1-5) 2. the sharing of the gospel with unbelievers (cf. Phil. 1:5) 3. the sharing of good things with others” 12 It is difficult to know exactly how the verse is to be interpreted. Perhaps the weight of evidence supports the idea that our faith becomes effective as we share the gospel. This is the approach of several Bible translations (ESV, NET, NKJ, NRS, & RSV).

The key word in this verse is that which is translated here as “partnership” (koinéōnia). This is the normal Greek word for “fellowship.” However, it has much broader meanings, including association, partnership, community and friendship.13 Obviously, to be effectual, our faith must be acknowledged and shared in various ways.

“Your love has given me great joy and encouragement, because you, brother, have refreshed the hearts of the Lord’s people” (1:7). It is clear from the Greek that Paul is talking directly to Philemon here. The apostle knows him well and Philemon has been an encouragement to Paul because of his great love. His love has refreshed many of God’s saints. Early Twentieth Century US evangelist William Godbey says, “The lordly mansion of this wealthy Asiatic was the rendezvous of God’s humble saints, where they worshipped in primitive simplicity radiant with the beauty of holiness, and enjoyed the generous hospitality of their kind host.” 14 “Hospitality was considered a paramount virtue in Greco-Roman antiquity, especially in Judaism.” 15

PAUL PLEADS FOR ONESIMUS

Therefore, although in Christ I could be bold and order you to do what you ought to do, Philemon 1:8

Paul knows that Philemon is a good, loving friend, so now he begins to lean upon him quite heavily. Paul needs a big favor from his good friend. He is aware that he has apostolic authority and that he could command Philemon at this point, but that would not be nice.

London Rector and scholar R. C. Lucas comments, “It would be impossible now to treat as a lesser being one who enjoyed such close fellowship with the great apostle.” 16 We do not know how long Onesimus had been with Paul, but it was long enough for the apostle to become greatly attached to him. He would like to keep him but he is no doubt aware of Roman law concerning escaped slaves. In Israel, escaped slaves were to be sheltered (Deut. 23:15-16) but in the Roman world they were to be promptly returned. The Roman culture was widely dependent upon slavery and escaped slaves were dealt with severely.17 To take someone’s slave was a little like taking someone’s car in our modern society.

Something brought this problem to a head with Paul. It has been suggested that it was the arrival of Epaphras. He was the founder of the Colossian church and other churches in the Lycus River Valley (Laodicea and Hierapolis). No doubt he had told Paul of Philemon’s faithfulness as well as about the heresy brewing at Colossae.18 Possibly, with his close associations at Colossae, he was able to recognize Onesimus and realize that he was the runaway slave of Philemon. It is also possible that the conscience of Onesimus had compelled him to make a clean break with his past.19

Paul continues, “yet I prefer to appeal to you on the basis of love. It is as none other than Paul— an old man and now also a prisoner of Christ Jesus—” (1:9). Here Paul refers to himself as an old man. The Greek word for old is presbutēs. In that culture this word described someone who was between 49 to 56. The word sometimes has a variation in spelling and could mean “ambassador.” 20 New Testament writers use the term more loosely for any person who is no longer young. Paul could have been 57, give or take five years.21

The apostle is here appealing to his age and to the fact that he is a prisoner. Scottish scholar and commentator, William Barclay, says: “Spoken to in such a way, could he do anything other than send Onesimus back to Paul with his blessing?” 22

Paul continues saying, “that I appeal to you for my son Onesimus, who became my son while I was in chains” (1:10). So, Onesimus, runaway slave of Paul’s dear friend Philemon, has somehow ended up in Rome with Paul and is ministering to the apostle in prison. He has become a believer and so dear to Paul that the apostle is now appealing for him from his friend. Apparently, Paul had won Onesimus to the Lord in prison, even while he himself was chained to a Roman soldier. He now considers Onesimus his own son. According to Rabbinic teaching, “If one teaches the son of his neighbor the law, the scripture reckons this the same as though he had begotten him.” 23

This appeal of love is at once placing Paul, Philemon and Onesimus all on dangerous ground. For Paul, Roman law required that Onesimus be returned to his owner or the apostle could face serious penalties.24 For Philemon, the Roman society expected that he would severely punish Onesimus. Runaway slaves could be beaten, branded on the forehead with the letter “F” (Gk. fugitivus) or even killed.25 It was not uncommon for fugitive slaves to be crucified. The reason for this was that the whole Roman economy was built on slavery. There were some sixty million slaves in the empire and the Romans constantly feared a slave revolt. Thus runaway of disobedient slaves were dealt with utmost severity.26 Of course, Onesimus was on dangerous ground most of all. He had no way of knowing how he would be treated by Philemon.

It is likely that some will object here about the whole subject of slavery. Certain people may chide Paul for not standing against the whole business. After all, Paul did teach: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28). He also said, “… there is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all” (Col. 3:11). Why didn’t Paul decree that all slaves should be freed? As we have mentioned, the whole Roman economy was based on slavery. For the church to have taught against it would have been disastrous. Lucas says, “It is probably nearer the truth to say that such a campaign would have indelibly stamped the new movement as a dangerous and revolutionary political force, to be ruthlessly crushed.” 27

It really took hundreds of years of Christian teaching to finally bring an end to slavery in most places. There are two ways to destroy a tree. We can take a chain saw and cut it down. In such case it will fall, probably crushing younger trees in the process. Or we can simply cut a circle around the tree (girdling) and in time the tree will die. The latter process may in the end make a lot more sense. Christian teaching by Paul and others cut a circle around the giant institution of slavery. It was doomed, but it would take hundreds of years for people everywhere to realize that fact.

“Formerly he was useless to you, but now he has become useful both to you and to me” (1:11). Onesimus was a very common slave name, with the meaning of “useful” or “profitable.” 28 Unfortunately, he had ceased to be either of these things for Philemon, although he was now both for Paul. The other words for useless (achrēston) and useful (euchrēston) found here sound very similar to each other but are from different Greek roots.29 Onesimus, whose name meant useful had become useless to his master. How this compares with our own lives. The reformer Martin Luther once said, “All of us are Onesimuses!” 30 In our natural state we are nothing, just slaves of the devil, but in Christ there is abundant hope and freedom for us all. Barclay adds to this: “It has been said that the most uplifting thing about Jesus Christ is that he trusts us on the very field of our defeat.” 31

A SLAVE AS A DEAR BROTHER

I am sending him— who is my very heart— back to you. Philemon 1:12

The word for sending is the Greek anepempsa, and it has the technical and legal meaning of “referring the case” to another person.32 In reality, it was a legal matter that Paul was referring. In addition to the legal matter, it was also a heart matter for the apostle. He dearly loved Onesimus and could not conceive of being without him.

Nevertheless, Onesimus had to go back to his master and face what he had done. Barclay says, “Christianity is not out to help a man escape his past and run away from it; it is out to enable him face his past and rise above it.” 33 Christians cannot dodge civil relations and responsibilities. Just because we are now free in Christ we cannot shirk our new Christian responsibilities.

The Bible gives specific instructions to believing slaves and to their masters. Slaves are instructed to submit and obey (Eph. 6:5; Col. 3:22; 1 Pet. 2:18). They are not to show disrespect to their masters (1 Tim. 6:2). They are not to obey only when their masters are looking but at all times (Eph. 6:5-8). Masters are to treat slaves kindly (Eph. 6:9) and they are to provide well for them (Col. 4:1). We must note that there are some very good guidelines here for employer and employee relationships today.

Paul was especially careful in sending Onesimus back home. He was accompanied by Tychicus (Col. 4:7-9). No doubt, this precaution was taken because he was a runaway slave and the slave-catchers would have been on the lookout for him.34 They probably operated much like our bounty hunters do today. Of course, a slave also could be stolen. An average slave was worth about five hundred denarii and a denarius was a day’s wage for a working man. Some slaves sold for a lot more if they were skilled or educated.35

“I would have liked to keep him with me so that he could take your place in helping me while I am in chains for the gospel. But I did not want to do anything without your consent, so that any favor you do would not seem forced but would be voluntary” (1:13-14). Paul dearly wanted to keep Onesimus and we can sense that throughout this letter. Such a thing was possible in Roman law. Slaves could be formally assigned to another person for a period of time and this was not uncommon.36 Just as some slaves were assigned to work in the temple of certain gods and goddesses, Paul is asking that Philemon might free Onesimus to labor in the gospel.37 Onesimus had served as a good substitute for the ministry Philemon might have done for Paul, had he been in Rome.

“Perhaps the reason he was separated from you for a little while was that you might have him back forever— no longer as a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother. He is very dear to me but even dearer to you, both as a fellow man and as a brother in the Lord” (1:15-16). Paul is suggesting that there might have been a divine purpose in the escape of Onesimus. When he left he was not useful and now, because of Jesus, he is. He left as a slave but he returns as a brother in Christ. Philemon now would be both master and brother in the Lord.

Some have called this verse the heart of the epistle, for in it we get a clear picture of what Christianity has done for the world. Barclay sums it up saying: “What Christianity did was to introduce a new relationship between individuals in which all external differences were abolished. Christians are one body whether Jews or Gentiles, slaves or free…When a relationship like that enters into life, social grades and classes cease to matter.” 38

PAUL ACCEPTS RESPONSIBILITY

So if you consider me a partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. Philemon 1:17

With the word “partner,” we once more run into the Greek word koinéōnon. We remember that this basic word can mean fellowship or even partnership. “Philemon and Onesimus were not only spiritual brothers in the Lord, but they had the same ‘spiritual father’ – Paul! (see Philem. 1:10; 1 Cor. 4:15)… God’s people are so identified with Jesus Christ that God receives them as he receives his Son!…” 39

“If he has done you any wrong or owes you anything, charge it to me” (1:18). A number of commentators feel that Onesimus must have stolen some things from Philemon before he made his getaway. Perhaps this was the case. If he had, Paul now agrees to pay the damages. Here we realize that Paul was not without a financial reserve. He was, after all, able to hire his own dwelling in Rome (Acts 28:30). On one occasion Felix thought he was even able to pay a bribe for his freedom (Acts 24:26). “With an affectionate smile Paul is saying, ‘Philemon, you got a lot out of me—let me get something out of you now!” 40

In ancient times when there was a letter acknowledging debt, there was usually a promise included that said something like this, “I will repay.” Such letters bore the signature of the debtor.41

“I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand. I will pay it back— not to mention that you owe me your very self” (1:19). Although it might have been difficult for him to see, some think that Paul may have written this whole epistle by himself.42 We might remember how it was customary for the apostle to employ an amanuensis or scribe to write his various epistles. Statements of obligation as we see in this letter carried legal validity in the ancient world. Paul is literally giving Philemon a promissory note which he vows to repay.43 Of course, he doesn’t miss the opportunity to remind Philemon of his own indebtedness.

“I do wish, brother, that I may have some benefit from you in the Lord; refresh my heart in Christ” (1:20). Commentators feel that there is really a hint here that Onesimus could be loaned to Paul.44 As we have seen, such an arrangement was possible under Roman law. We cannot know how things turned out, but this once runaway slave could have been reinstated and assigned as a co-worker with the great apostle Paul.

“Confident of your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I ask” (1:21). Chrysostom (c. 349 – 407) remarks about this statement saying, “What stone would not these words have softened?” 45 If Philemon actually did more than Paul asked he may well have assigned Onesimus to the service of Paul. To do more than the apostle asked is hinting that the slave might be set free entirely.46

CLOSING REMARKS

And one thing more: Prepare a guest room for me, because I hope to be restored to you in answer to your prayers. Philemon 1:22

Philemon was a generous person who was known for his benevolence, so Paul asks of him another favor. He expected to be released from his confinement soon and he planned to come to the Lycus Valley area. He desired to lodge with Philemon and his family. This was a customary practice for Christians in the First Century. The inns were few and the ones that were available were expensive and ill kept. They were often havens of prostitution. So, Christians lodged with other Christians when traveling. Well-to-do patrons like Philemon were expected to provide hospitality and receiving a prominent guest like Paul was considered an honor in those days.47

Paul had been in confinement for two years but he fully expected to be released soon (cf. Acts 28:30; Phil. 2:24). It seems that Paul was actually released and that he carried on more mission work. This seems apparent from hints in the Pastoral Epistles. It is highly likely that he even undertook a mission to Spain. However, one of the first trips after his release was surely to Colossae or to other of the Lycus Valley churches.

“Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends you greetings” (1:23). We see Epaphras mentioned here and in Colossians 1:7 and 4:12. In these scriptures we are told that he is a faithful minister of the Lord. Since the very same persons that are mentioned here are mentioned in Colossians, there is evidence that Philemon resided at Colossae.48 It is clear here that Epaphras had volunteered to do some jail time with the apostle. It is possible that his name was the shorter form of Epaphroditus. We see another man by this name mentioned in Philippians 2:25; 4:18, but this person was from a different geographic area.49

“And so do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas and Luke, my fellow workers” (1:24). Mark is no doubt John Mark, the nephew of Barnabas (Acts 12:12, 25). As a youth he had turned back on Paul’s First Missionary Journey. For this reason Paul would not consent to take him on the next journey (Acts 15:37-39). However, Mark proved himself and was later able to work with the apostle. As Paul was in prison the second time and nearing the end of his life, he desired that Mark be brought to him (2 Tim. 4:11). Here we see both Mark and Luke with Paul and they were apparently with him as he approached his end. It is interesting that two of the later gospel writers worked closely with Paul and obviously spent some prison time with him.

Here Demas is mentioned, but nothing is said about him. In the end, he would desert Paul because of his love for this present passing age (2 Tim. 4:10). His apostasy is surely one of the saddest stories in the New Testament. Aristarchus was a faithful worker who had seen some tough times with Paul (Acts 19:29). He also accompanied Paul and endured the shipwreck on the journey to Rome (Acts 27:2).

“The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit” (1:25). This benediction is both short and beautiful. Wright says of this little epistle: “No part of the New Testament more clearly demonstrates integrated Christian thinking and living. It offers a blend, utterly characteristic of Paul, of love, wisdom, humor, gentleness, tact, and above all Christian and human maturity.” 50

As we close, it might be encouraging to recall some information from the early church father Ignatius, who about fifty years later was on his way to martyrdom. As his journey progressed he wrote a letter to the church at Ephesus and to their wonderful bishop. Interestingly, the bishop’s name was Onesimus. Curiously, Ignatius makes the very same pun that Paul made, about his name and work now being profitable to God. In those days when slaves sometimes served as pastors, could it be that this once runaway slave was now the great Bishop of Ephesus? 51

_________

FOOTNOTES PHILEMON

Several sources I have cited here are from the electronic media, either from websites or from electronic research libraries. Thus in some of these sources it is not possible to cite page numbers. Instead, I have cited the verse or verses in Philemon (e.g. v. verse 1:1 or vs. verses 1:5-6) about which the commentators speak.

INTRODUCTION

1 William Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1975, 2003), pp. 303, 310.

Lucas adds: “Paul’s letter to Philemon is one of the special treasures of the NT. It is of unique interest to us as the only surviving example, from the apostle’s no doubt vast correspondence, of a letter to an individual friend and convert.” (Lucas, p. 184).

Barker & Kohlenberger also add: “Few if any dispute that Philemon was written by the apostle Paul…This letter appeared early as a letter of Paul in the Muratorian fragment and in Marcion’s canon….” (Barker & Kohlenberger, p. 935).

CHAPTER 1

1 R. C. Lucas, The Message of Colossians & Philemon (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 1980), p. 190.

Utley adds: “Paul was in jail in the early 60’s and this is recorded in Acts. However, he was released and wrote the Pastoral letters (1 & 2 Timothy and Titus) and was then rearrested and killed before June 9, AD 68 (Nero’s suicide). The best educated guess for the writing of Colossians, Ephesians, and Philemon is Paul’s first imprisonment, early 60’s.” (Utley, v. 1:1).

2 Peter Gorday, ed., Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, IX, Colossians, 1-2 Thessalonians, 1-2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 2000), p. 310.

3 John Trapp, John Trapp Complete Commentary, Commentary on Philemon, 1865-68, v. 1:1. http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/jtc/view.cgi?bk=56&ch=1.

4 Kenneth L. Barker & John R. Kohlenberger III, Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary, Vol. 2 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994), p. 936.

5 Charles F. Pfeiffer & Everett F. Harrison, The Wycliffe Bible Commentary (Chicago: Moody Press, 1962), p. 1397.

Barclay adds: “Archippus…He appears in both Colossians and Philemon. In Philemon, greetings are sent to Archippus, our fellow soldier…and such a description might well mean that Archippus is the minister of the Christian community…” (Barclay, p. 307).

6 Warren W. Wiersbe, The Wiersbe Bible Commentary, NT (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook, 2007), p. 79.

7 Dr. Bob Utley, Free Bible Commentary, v. 1:2.

http://www.freebiblecommentary.org/new_testament_studies/VOL08/VOL08.html7

8 Ibid.

9 David Guzik, Commentary on Philemon, David Guzik Commentaries on the Bible, 1997-2003, vs. 1:2-3. https://enduringword.com/bible-commentary/philemon-1/

Lucas adds: “The ‘you’s’ and ‘yours’ of the greeting (verse 3) and conclusion (verses 22-25) are plural. So it is evidently an open letter, to be received and read by the church in Philemon’s house as well…” (Lucas, p. 184).

10 Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1993), p. 645.

“Paul kept times of regular prayer, a normal pious Jewish practice (probably at least two hours a day)…”

11 Tertullian, Apologeticum, ch. 39, 7.

12 Utley, Free Bible Commentary, v. 2:6.

13 William Barclay, A New Testament Wordbook, (London: SCM Press LTD, 1955, 1959), pp. 71-72.

14 William Godbey, Commentary on Philemon, William Godbey’s Commentary on the New Testament, v. 1:7. http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/ges/view.cgi?bk=56&ch=1

15 Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament, p. 645.

16 Lucas, The Message of Colossians & Philemon, pp. 190-91.

17 D. Guthrie, et. al., The New Bible Commentary, Revised (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1970), p. 1187.

18 Utley, Free Bible Commentary, v. 1:8.

19 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 304.

20 A. T. Robertson, Commentary on Philemon, Robertson’s Word Pictures of the New Testament (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1932, 33, Renewal 1960), v. 1:9. http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/rwp/view.cgi?bk=56&ch=1.

Utley adds: “Scholars have pointed out that in Koine Greek the term ‘the aged’ and ‘ambassador’ (presbeutēs) may have been spelled the same or at least often confused (cf. MSS of LXX; 2 Chr. 32:31). The English translations TEV, RSV, and NEB have ‘ambassador,’ while NJB and NIV have ‘an old man.” (Utley, v. 1:9).

21 Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament, p. 645.

22 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 309.

23 Cited in Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 317.

24 Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament, p. 644.

25 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 305.

26 Ibid.

27 Lucas, The Message of Colossians & Philemon, p. 189.

28 Barker & Kohlenberger, Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary, Vol. 2, p. 937.

29 James Burton Coffman, Commentary on Philemon, Coffman Commentaries on the Old and New Testament (Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press, 1983-1999), v. 1:11. Citing Lenski. http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/bcc/view.cgi?bk=56&ch=1.

30 Quoted in Warren Wiersbe, The Wiersbe Bible Commentary, NT (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook, 2007), p. 798.

31 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 318.

32 Pfeiffer & Harrison, The Wycliffe Bible Commentary, p. 1398.

33 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 318.

34 Coffman, Commentary on Philemon, Coffman Commentaries on the Old and New Testament, v. 1:12.

35 Wiersbe, The Wiersbe Bible Commentary, NT, p. 798.

36 Barker & Kohlenberger, Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary,Vol. 2, p. 937.

37 Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament, p. 646.

38 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 306.

39 Wiersbe, The Wiersbe Bible Commentary, NT, p. 799.

40 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 320.

41 Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament, p. 646.

42 Albert Barnes, Commentary on Philemon, Barnes’ Notes on the New Testament, 1870, v. 1:19. http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/bnb/view.cgi?bk=56&ch=1.

43 Barker & Kohlenberger, Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary,Vol. 2, p. 938.

44 Ibid., p. 939.

45 Gorday, ed., Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, IX, Colossians, 1-2 Thessalonians, 1-2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, p. 317.

46 Guthrie, et. al., The New Bible Commentary, Revised, p. 1190.

47 Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary, New Testament, p. 646.

48 Barnes, Commentary on Philemon, Barnes’ Notes on the New Testament, v. 1:23.

49 Utley, Free Bible Commentary, v. 1:23.

50 Quoted in Guzik, Commentary on Philemon, David Guzik Commentaries on the Bible, v. 1:25.

51 Barclay, The Letters to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, p. 310.

“Why did this little slip of a letter, this single papyrus sheet, survive; and how did it ever get itself into the collection of Pauline letters?…It is practically certain that the first collection of Paul’s letters was made at Ephesus, about the turn of the century. It was just then that Onesimus was Bishop of Ephesus; and it may well be that it was he who insisted that this letter be included in the collection…”

Guzik adds: “If Onesimus was in his late teens or early twenties when Paul wrote this letter, he would then be about 70 years old in A.D. 110 and that was not an unreasonable age for a bishop in those days.” (Guzik. Conclusion).